At Atigun River, north of the Arctic Circle, the sandy soil is run through with an interlaced network of burrows. The Arctic ground squirrels which call those burrows home have encountered something mundane to you or me, but no-doubt wondrous to them: big tasty taproots, stunningly orange. Carrots!

Trapping squirrels

The carrots are bait, placed carefully in wire cage traps by scientists working to learn more about the very unusual Arctic ground squirrel. Cory Williams, postdoctoral fellow at the University of Alaska Anchorage, studies circadian and cirannual rhythms in Arctic ground squirrels.

“To catch Arctic ground squirrels we use live tomahawk traps. We bait them with carrot and squirrels essentially enter through the entrance; there’s a little treadle that they step on and the trap closes behind them. So we are able to capture them quite easily. We don’t see a lot of trap avoidance with the ground squirrels. We do have some squirrels that become trap happy: they understand there is food in traps, so they actively seek them out and we catch them more often than you would expect. They love the carrots.” ~Cory Williams

Kate Wilsterman, who began studying Arctic ground squirrels as part of the National Science Foundation’s Research Experience for Undergraduates program, works with Cory Williams and Loren Buck, University of Alaska Anchorage Department of Biological Science professor, to catch and study squirrels. She describes what happens after an Arctic ground squirrel is captured in a trap.

“The handling bags are actually custom made. They have netting in the middle, either end is fabric, the latter has elastic around it. You put that on the end of the cage, pull open the door, then the animal runs to the netted part. You close the bag behind him. And then you can look for his ear tag, handle him. Afterward you open up the far end and he runs through.” ~ Kate Wilsterman

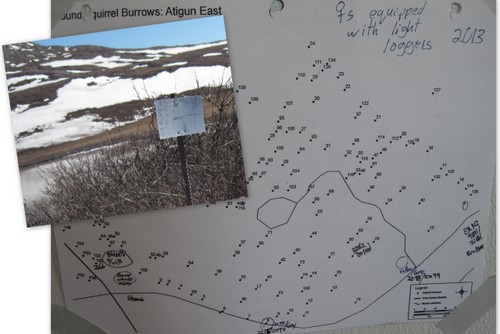

The squirrels are checked for ear tags with identifying numbers and colors. The researchers record their gender and feel the females’ abdomen to check for pregnancy. They take the squirrels’ weight and record on a map what burrow they were captured next to. Any animals that are transported to the lab are later returned to their home burrows.

Bright light at Toolik

The scientists researching Arctic ground squirrels, ‘Team Squirrel’, used a summer lab based out of Toolik Field Station in Alaska’s North Slope, not so far from the Atigun River research site. Toolik Field Station is funded by the National Science Foundation and operated by the University of Alaska Fairbanks Institute of Arctic Biology. It hosts scientists from all sorts of disciplines as they decode the secrets of a rapidly changing Arctic.

The summer Sun in the Arctic never sets below the horizon. Where most animals (including most humans, if we were on vacation) would respond with a free form drifting schedule, eating when hungry and sleeping when tired, Arctic ground squirrels don’t. Their internal clock function maintains a regimented schedule. Bedtime no later than 10:00pm!

PolarTREC educator

Alicia Gillean is a PolarTREC teacher, an educator selected to spend time with scientists in the field. In 2013 she worked as part of Team Squirrel, getting hands-on experience with the science and then developing educational resources and communicating the science back to the 5th and 6th grade students of Jenks West Intermediate School in Oklahoma. Those resources are freely available online. It’s a great way to get students exposed to more science and thinking about STEM careers.

PolarTREC stands for: Teachers and Researchers Exploring and Collaborating. The PolarTREC project Arctic Ground Squirrel Studies (2013) has an overview page which talks about clock function:

“Circadian rhythms refer to the “internal body clock” that regulates the approximately 24-hour cycle of biological processes in animals and plants. Rhythms in body temperature, brain wave activity, hormone production, and other biological activities are linked to this 24-hour cycle. The Earth’s light-dark cycle provides the strongest influence on circadian rhythms and is thought to be the primary driver for the emergence and evolution of internal clocks.” ~PolarTREC, Courtesy of ARCUS

Here’s a FrontierScientists video featuring Team Squirrel scientists: Arctic Ground Squirrels And The Circadian Clock.

Technological tools

Besides carrots, traps and maps, eartags and observation skills, Team Squirrel makes good use of modern technology to help decode the Arctic ground squirrel’s clock function.

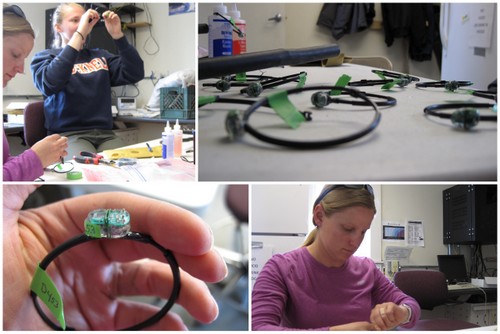

Some squirrels are chosen to be temporarily fitted with tiny collars carefully coated with cushioning rubber and affixed with a photo sensor. The photo sensor measures the amount of light the squirrel is exposed to and when. Once it’s recovered and the data is downloaded, the researchers gain a record. When was the squirrel above ground in the unpredictable weather foraging for food and evading predators? When was the squirrel below ground in a (relatively) cozy burrow caching food, nursing young, or sleeping? Adult squirrels are better candidates for the photo sensors because they have more experience avoiding predators than juveniles do, so the data record is less likely to be cut short by a golden eagle, fox, wolverine, wolf, or bear (what a list!). The collar might also carry a radio transmitter if it’s particularly important that the scientists be able to quickly find an individual Arctic ground squirrel that’s part of an experiment.

The scientists also make use of a tiny device which measures and records body temperatures. Knowing an Arctic ground squirrel’s body temperature record lets scientists decode their metabolic activity. A cooler temperature denotes sleeping times then temperatures increase just before waking as the metabolism prepares for the day, and active foraging and running about ramp up temperature further. The data logging device is surgically implanted while the squirrel is anesthetized, very similar to the Passive Integrated Transponder tags you can have implanted in your pet, and then later explanted (removed).

Gillean has a very excellent account of what procedures are followed while a temporarily anesthetized squirrel is being handled in the lab in her journal: Earning a ticket back to the lab.

She also describes an experiment in which Team Squirrel phase shifted eight Arctic ground squirrels so the animals’ clock function would temporarily schedule their awake period during the night. Ground squirrels are normally diurnal like humans: they are awake and active during the daytime, the hours centered around noon. By keeping some in a lab and controlling the lighting, the scientists slowly rotated ‘day’ until it corresponded to night-time, the hours centered around midnight. They used special water and little blood samples obtained through toenail clipping to estimate the squirrels’ energy expenditure. Perhaps the reason most squirrels are active around noon is because they expend slightly less energy staying warm or avoiding active predators.

Gathering data

“At first glance, it looks like the squirrels bounced back to their normal schedule almost immediately. It will require additional data from implanted body temperature loggers, further analysis of the light logger data from all animals in the experiment, analysis of the blood samples, and more before any real conclusions can be drawn. It is interesting to study the data and try to figure out the story that it tells!” ~Alicia Gillean

Gillean’s Arctic ground squirrel story, as well as great advice she collected from scientists to give to 5th and 6th graders, are wonderful ways to bring ongoing research on these distant but adorable subjects to life for students and potential future scientists.

Laura Nielsen

Frontier Scientists: presenting scientific discovery in the Arctic and beyond

Arctic Ground Squirrel project

- Alicia Gillean’s account of Arctic Ground Squirrel Studies, PolarTREC (2013)

http://www.polartrec.com/expeditions/arctic-ground-squirrel-studies - Interviews with quoted scientists, 2013 & 2014