Laura Nielsen for Frontier Scientists –

Snowball fights. Snow angels and lovely ice sculptures. You can truck across it or ski through it. Snow might be a heavy reality you shovel every day, or a glittering crystalline landscape far away. Or both. Whatever snow means to you, it means something much more complex to the world. Snow is powerful and volatile. It governs ecosystems in the far north and impacts climate across the globe. At FrontierScientists, the scientists who are working hard to refine our understanding of snow melt are featured in our new project Arctic Snow.

Area versus volume

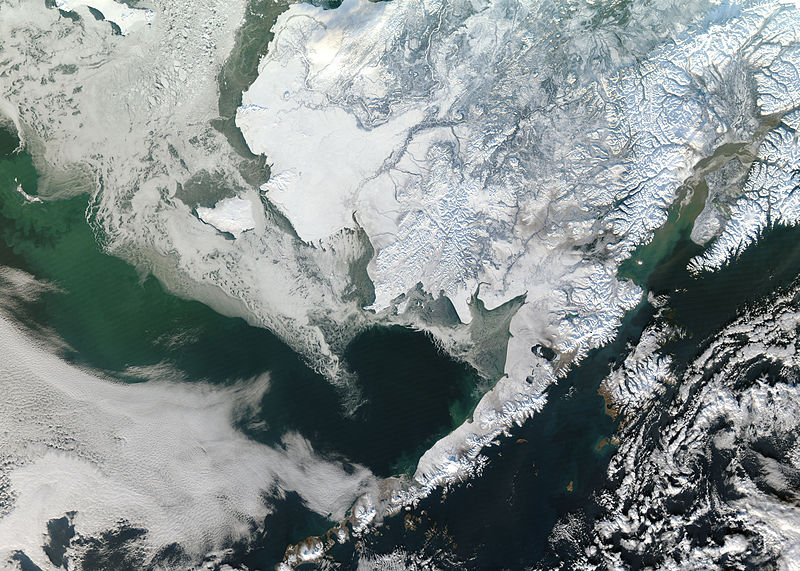

The Arctic is covered in snow that accumulates in August and doesn’t melt away until June. That’s the natural state of affairs. Snow is white and the Arctic is white.

The region is vast and unforgiving, so the most expansive measurements of snow cover there come from satellites. NASA’s Terra and Aqua Earth-viewing satellites carry instruments called Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometers. MODIS instruments survey images of land in 15.5 mile (25 kilometer) long segments. The instrument that predated MODIS, AVAHR, looked at stretches of land 124 mile (200 kilometer) long. From those huge ranges, we determine and record whether the land was snow covered or snow free.

The studies at Imnaviat Creek, north of the Brooks Range in Alaska, have measured snow melt since 1984… representing the longest ongoing record of snowmelt and runoff. Scientists there can tell you it’s never a uniform melt. Snow melt is a process; it clears out patchily, leaving some ground exposed to the sky while other areas are still cloaked in snow so deep the researchers must wear snowshoes. That’s why satellite measurements which scan large areas can’t accurately gauge snowmelt. Furthermore, while satellite records tell us about snow cover extent, they can’t record how much snow there is because it’s extremely difficult to measure volume from space. On-the-ground data is better for measuring snow depth and density.

Matthew Sturm, geophysics professor at the Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, calls the Imnaviat Creek studies a ‘reality check’ and names it a ‘ground-truth spot’, a place that can help us refine our understanding of snow and how we interpret snow data. Recording the melt variations in Imnaviat Creek basin can give scientists the data they need to integrate on-the-ground snow behavior and satellite records into larger models.

Timing

Most of the Arctic is covered in white. Snow cover, sea ice, ice sheets and glaciers cap the world: a glittering wonderland. Sturm notes that when open ground is showing that’s the exception, not the rule. The time when Arctic soil is exposed to the sun is growing, though, and even if you live far from the North that fact matters to you.

You’ve probably seen the news about the dramatic loss in sea ice extent. Ice floes break apart and melt, exposing dark ocean water. There’s even a NOAA webcam pointed at the North Pole, and you can watch open water form melt ponds on the ice. It’s drastic.

Something similar is occurring with snow. Even in Alaska’s far north the timing of smowmelt is changing, occurring several weeks earlier than it used to. The area that snow covers in the Arctic is reducing by about 2% each year— that’s a new area about the size of Nebraska left open to the sky per year.

Arctic snow melts in June when sunlight is strongest in the Northern Hemisphere. The far north is exposed to summer-season light that never ceases because the sun never sets below the horizon. That means plenty of solar energy is entering the atmosphere.

Snow and world climate

Light-colored snow and ice have a high reflectiveness, also called a high albedo. They reflect sunlight that reaches the Earth right back into space. As Sturm notes, a whiter world is a colder world. Without snowcover, the open ground or open ocean have a much lower albedo and they absorb the heat of the sun instead of reflecting it. It’s just like hot car seats that have warmed up under summer sun.

Snowcover reflects about 90% of solar rays. Uncovered ground? Only about 10%. So in June when the snow melts away and the summer sun is rampant in the Arctic sky, the entire Arctic is absorbing more energy and more heat.

Earlier melt times and less snow cover extent means more open ground with a low albedo. Open tundra absorbs plenty of heat. That impacts global climate. Snow plays an important role in governing the energy balance of the entire world’s climate.

Snowcover also serves as a safety shield for permafrost. Permafrost is what we call the layers of soil in the Arctic that are always frozen (well, almost always). Winter temperatures are so low that they freeze the ground solid. Summer temperatures might melt the highest layers of the permafrost, but more frozen soil underlies those layers and keeps the ground hard and cold. Since the soil is frozen and adequate sunlight is limited to summer months, only very stubborn low-growing plants grow on the Arctic tundra. When the plants die, their remains often get incorporated into a new layer of frozen soil. Just like food in the freezer, the frozen permafrost layer doesn’t decay unless it melts.

Snow prevents permafrost from melting because it shields it from the sun’s energy. In the summer, though, melt water percolates down to the soil and leeches in. At Imnaviat Creek the soil thaws to a depth of only 20-30 inches (50-90 centimeters). When melt occurs earlier, the permafrost has more time to heat under the sun’s rays and melt, leading to deeper layers of thawed ground.

Permafrost matters because it stores immense amounts of carbon and methane. Plants take in carbon dioxide (CO2) during photosynthesis, then release oxygen. They store and use the carbon. Dead plants locked in frozen permafrost never decompose, which mean the carbon stays trapped in their remains. The permafrost melting in our hotter world allows ancient organic matter to decompose, which releases carbon and methane (another greenhouse gas) into the atmosphere.

Life in a snow-governed habitat

The Arctic’s vast icy expanse isn’t a dead place. Life exists even below the snow. And the timing of the snowmelt governs local ecosystems. The snow melt triggers plant growth, flower blooms, and insect activity.

Snow that has settled on the ground transforms. Deep snow partially melts and reforms into large icy crystals. Packs of those large ice crystals composes depthhoar— the Native Inupiat word is for it is pukak. Small mammals inhabit the pukak, digging tunnels and dens, stashing seeds, and living their lives. Lemmings— which den under the snow— are a keystone species in the Arctic, and their lives change drastically when the snow melt timing changes.

The great caribou herds migrate based on the snow’s schedule, seeking plant life to graze on. When they stand in soil inundated by snow melt water, they are at risk to lightning strikes. When an early melt date makes the summer stretch long and temperatures are high, though, the tundra dries out and lightning strikes can cause wildfires which release huge amounts of carbon into the air.

These animals are not alone. Visitors from the south fly in when the snow melts. Migratory birds flock to Alaska in the spring to breed and feed before they fly back south to overwinter in warmer climes. The timing that decides their migrations isn’t entirely understood, but we do know that sometimes the timing is off. A bird species might fly in when their favorite food source used to bloom, only to find that time has already passed because of an early snow melt. It’s called trophic mismatch, and it might spell trouble for species all across the globe if they can’t adjust to modern-day climate change.

Studying snowmelt at Imnaviat Creek

Imnaviat Creek, like most of Alaska’s small creeks, collects water from melting snow and flows out toward the ocean. Researchers there have seen snow melt happen in as little as six days… six days from winter snow cover to open ground. The melt water influx introduces a whole lot of water into Alaskan waterways, and can cause flooding. Understanding the process and studying hydrology there teaches us about flooding from Arctic snow melt and helps keep communities safe.

It’s a tough job: living in temporary field accommodations in Alaska’s unpredictable weather, walking over the Arctic basin’s slopes and deep snow on snowshoes. Researchers traverse a long path wearing snowshoes, taking measurements in the untrodden snow at the side of their path. They record snow depth and GPS location. With coring tubes, they capture cylinders of snow and weigh them to discover how much water is in the snow (because snow can have different densities and hold different amounts of water). They collect aerial photos to catalog the snow distribution and collect data for software that can model the topography of the snow surface. They also measure the water that flows away via Imnaviat Creek to understand how much water is leaving the system and how much is thawing layers of soil, sinking in, and sitting atop deeper permafrost.

All that, and they’re not always funded. The continuous record of this particular study is so important that researchers have been passionate enough to continue it unsupported. That’s dedication. Imnaviate Creek snow melt data can refine our interpretation of snow melt trends in the Arctic and teach us how snow alters and is altered by our shifting climate.

Frontier Scientists: presenting scientific discovery in the Arctic and beyond

Watch: Snow is White

Watch: Imnaviat Creek SnowMelt