Imagine yourself on a Colorado mountain slope. Bumblebees buzz happily around dwarf bluebell blossoms, and the spring sun is bright. Except not all is well. The flowers bloom a good seven hundred feet upslope of where they grew five years ago, forcing bees ever higher. Bright petal colors are faded: the flowers are past their prime, plants already flagging. And broad-tailed hummingbirds are only now arriving from their northward migrations. Their customary feast of subalpine glacier lillies normally just opening as the birds arrive- begain their bloom seventeen days ago, and many are already withered.

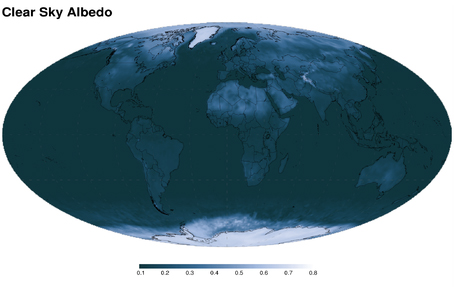

What has gone wrong? Mountain snow melt is beginning earlier and earlier. An not only heightened temperatures are to blame. Dust from the over-grazed American Southwest and other particulate matter like black carbon (an ugly side-affect of burning coal) lands atop the snow. Those dark layers reduce snowcover’s albedo, or solar reflectiveness. No longer reflected back into space, the sun’s heat zeroes in on the darkened snowpack. Dust dramatically accelerates snowmelt.

“The extremes are changing,” notes Heidi Steltzer. Steltzer, Fort Lewis College in Durango Colorado, and David Inouye, University of Maryland and Rock Mountain Biological Laboratory biologist, presented a session entitled “When Winter Changes: Hydrological, Ecological, and Biogeochemical Responses” at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting 2012. The National Science Foundation -funded work asks Where Have Our Winters Gone? and investigates how earlier onset of spring threatens ecosystems and water resources.

Early snowmelt has profound effects on plants. The disappearance of the snowpack triggers the growing season. Many alpine plants will begin growth about ten days after snowmelt, and flower about twenty days after. Steltzer notes that plants “Evolved to run, not walk,” and have no way of delaying this automatic process. If the snowpack disappears in mid May instead of late June, blooming flowers face threats like cold snaps that kill buds, or shortage of water because Colorado monsoons bring rain in July. The blossoms attain their peak and begin to wither before pollinators like bees, migratory birds, and small mammals are necessarily present. This leads to decreased seed production.

Things are out of sync. While pollinators struggle to meet the challenges of their altered habitat, only so much adaptation is possible without evolutionary change, and climate change proceeds too speedily for that. Bees can’t use alarm clocks, and migratory birds can’t always continue to thrive when their world changes. Creatures struggling to adapt to altered biomes are starting to push the limits.

Humans are pushing the limits too. Early snowmelt means a glut of water in the spring season. Reservoirs overflow. Later in the summer, when farmers in the Colorado watershed need it most, there is a dearth of water. Agricultural lands dry up.

Scientists at the Colorodo Dust-on-Snow program (part of the Center for Snow & Avalanche studies) are gathering data. They measure the dust which settles on snow cover, especially after dust storms, and track the snow melt. Datasets can help researchers build climate models which account for snowmelt, dust, and runoff. Run on supercomputers, these climate models will aid in future water management plans.

When we look north, we can see in the Arctic Circle a huge solar mirror. Pristine snow can reflect about 90% of sunlight back into space, ocean ice about 70%. If either darken from particulate deposits like dust, or melt because of heightened temperatures, the overall albedo (solar reflectivity) in the Arctic decreases. The Arctic takes in more heat. More Arctic heat increases world temperatures, and heightened world temperatures mean more Arctic ice melt. It’s a positive feedback loop of warmth.

A similar feedback loop is occurring in the Colorado mountains. Intensified land use in the Southwest including grazing and human development cause dust to kickup. The airborne dust coats mountain snow, which forces a faster melt of snowpack. Early melt drains away water reserves early, leading to summer drought, which in turn causes more dust. Dust can arrive from elsewhere too: carried from desertified African lands, from China’s Takla Makan Desert or the Gobi Desert. Where this type of loop occurs, we face threatened ecosystems, water insecurity, and heightened fire risk.

It is heartening to remember that lessons from the Dust Bowl prompted the Taylor Grazing Act (1934) which would eventually result in the Bureau of Land Management, reducing desertification and dust from America’s Southwest. And the Clean Air Act (1970) vastly reduced coal pollution and particulates including black carbon. In our rapidly changing world, we’ll have to continue to recognize problems and look to solutions.

Find much more on Arctic Birds, Computational Science, Climate Change, and other Arctic science at Frontier Scientists

Laura Nielsen 2013

Frontier Scientists: presenting scientific discovery in the Arctic and beyond